The closer we are to an epoch, the more difficult it is to comprehend its essential traits: we know at once at too much and too little.

—George Lichtheim

Contents of this chapter

This memoir has largely been about interactions: some connecting across thousands of miles, others occurring day after day in a single office. Rich interactions took place in the first office I came to, the eccentric Brickyard on Sherman Street, where the bulk of the stories in this chapter take place. By the time of the big layoff, the East Coast office of O’Reilly was in Downtown Crossing, Boston, but I never had a desk there. I was working remotely by then. I did my best to keep strong relationships with other employees, forged over years of close collaboration, but these ties gradually frayed at the building we occupied before Downtown Crossing: a conventional office complex on Fawcett Street, on the western side of Cambridge, to which we moved in the early 2000s. The culture there eventually whittled away any motivation I had to come into the office.

I had nothing against Fawcett Street. The setup was cozy for me, as I lived in the next town over. A ten-minute bus ride would take me to work (twenty minutes perhaps, when Cambridge’s highly resented rush-hour traffic choked the main roads), but usually I walked. My fifty-minute walking route took me through a forest and by a pond. After the sounds of the woods receded, I inserted earplugs and listened to MP3 files that I had ripped from CDs. I then traversed a suburban landscape that gradually grew more crowded until I was right across from the woods of Fresh Pond park.

In the winter, I put on snow grips and bypassed the forest. Although a few years before I had broken my ankle falling on ice, I overcame my fear of the winter weather. The only time the commute was difficult was when the city of Cambridge tore up Concord Avenue for years on end right next to our building, and eliminated the sidewalks on both sides. I can now issue my final piece of advice in this memoir: Don’t make a habit of dodging Cambridge automobile traffic.

Another nice thing about Fawcett Street was my personal office, an office space I loved for a job I did not like. I associate the space now with the mid-2000s slump I have described elsewhere. But I enjoyed the office’s repose. It was tucked into the corner of the building, right opposite the stairs I used to access the office (I climbed the four flights for exercise) and far removed from most of the bustle on the floor.

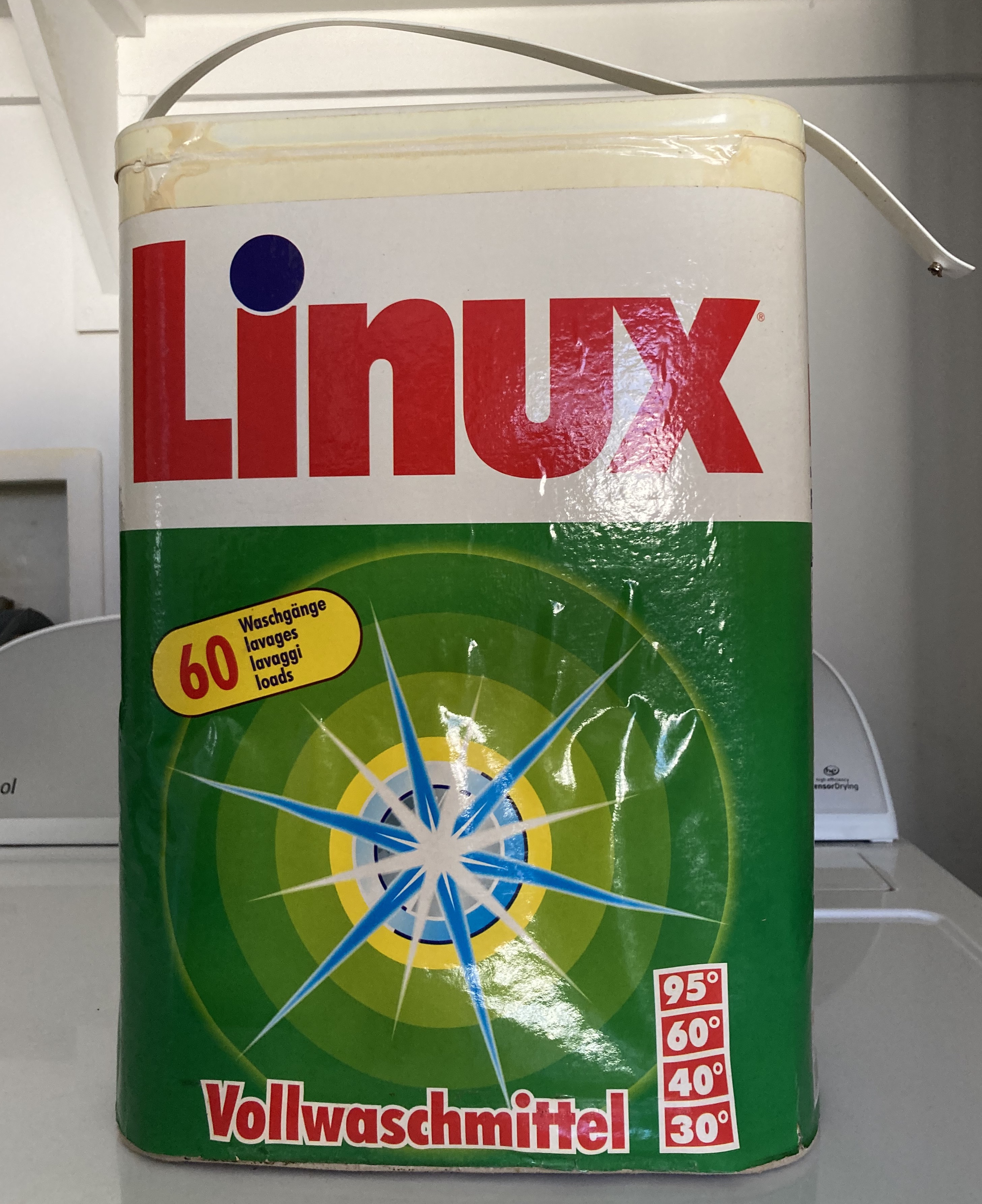

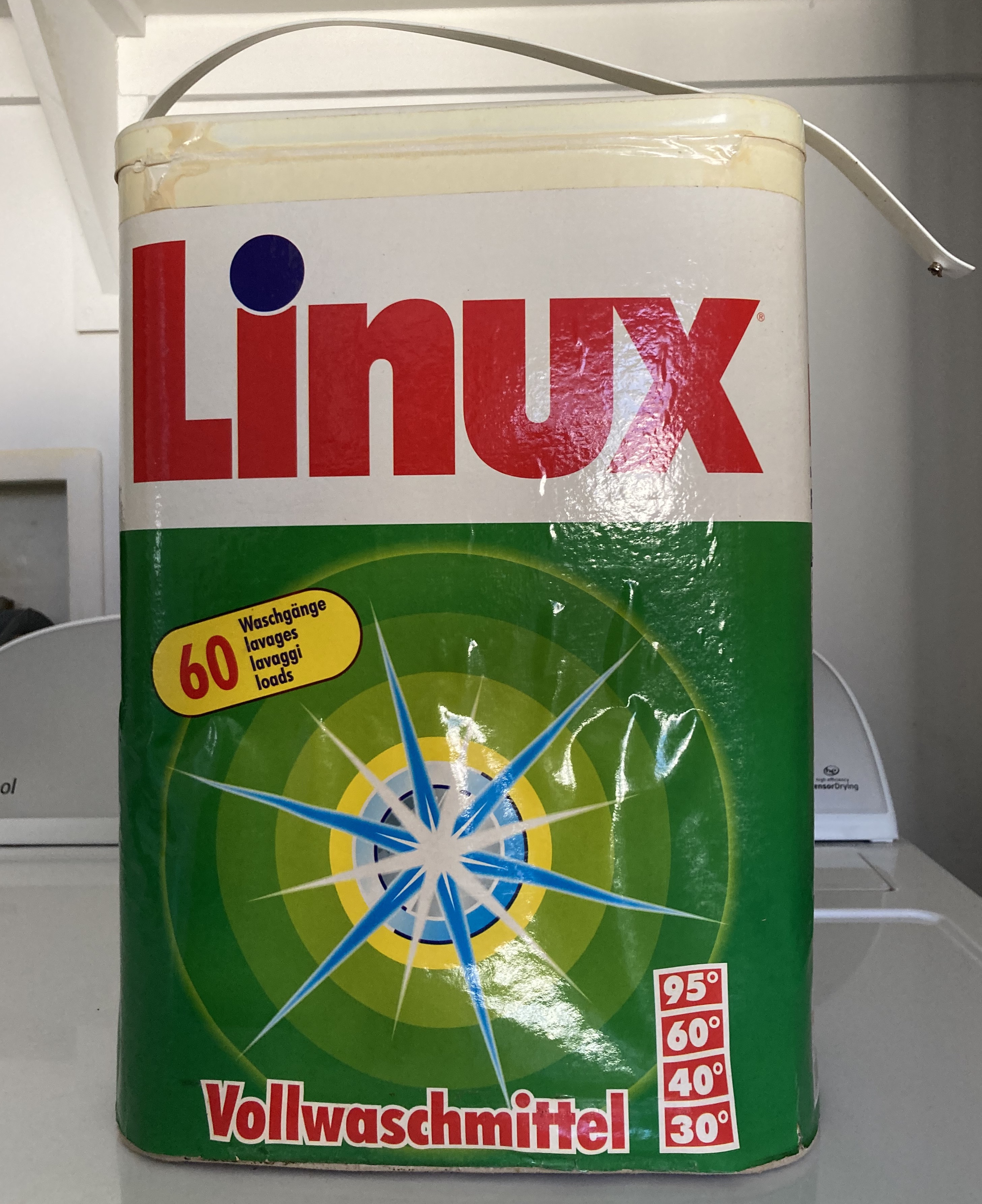

I decorated the walls of this office with memorabilia that held meaning to me, including a painting by Judy, and displayed oddities I had picked up over the years, notably an enormous empty soapbox bearing the name “Linux”. (Yes, a German company had irreverently decided to use the name to sell soap, managing to sidestep trademark issues. They earned worldwide fame for this marketing ruse, even though nobody bought the product. Germans are very particular about their soap, and my friends in our Köln office told me that the Linux soap had earned a poor reputation.) I could also display a two-foot-high glass penguin in bilious yellow that I won at a trivia contest at the 2004 LinuxWorld conference.

The office was rounded out by a gawky desktop computer running the GNU/Linux distribution of the day—recalcitrantly bending to my will when I exerted enough mental force—and a copious bookshelf collecting translations of my edited works into languages I could read and those I could not, old books from O’Reilly and other publishers that I had found useful at one time or another, journals, and other mostly worthless historical artifacts.

The only drawback of my office was that the window faced north onto Fawcett Street instead of south toward the lovely trees of Fresh Pond. The view of parking lots and boxy buildings was not aesthetically notable but historically inspiring, because I could see right onto one of the old buildings of Bolt Beranek & Newman, later after a break-up to have the name Genuity slapped on before the whole edifice was finally replaced by a more modern structure. I could swell with excitement at being a few yards from the ground where stood the company that designed the Internet, after performing other equally critical technical roles during World War II.

The challenge of moving to Fawcett street was that of keeping our minds supple and creative while leaving behind the funkiness of Sherman Street, which I compare to the atmosphere of a college dorm. Certainly, the new space conformed more to the look professionals expect an office to have. We didn’t have to deal with leaks from the ceiling anymore, and our electricity use no longer had to beg the wiring for cooperation. This was probably a necessary move.

However, the building at Fawcett Street had its own little lapses. You needed a card to enter the employee garage, which in our popular Cambridge location was a worthwhile control measure—but why did you also need a card to leave the garage? This made things difficult for visitors and security staff.

And then the smart lights. The building’s management thought it would be a great energy-saving measure (such things are perennially of interest in the city of Cambridge) to place sensors that turned overhead lights on when people enter the room and thriftily shut them off when the room was empty. But the sensors were merely motion detectors, by no means designed for the purpose to which the building put them. If you worked quietly for five or ten minutes, the lack of motion convinced the light that the room was empty, and suddenly you couldn’t see anything but the glowing computer screen. I saw one employee develop an automatic habit of nodding her head every few minutes, in order to trigger the motion detector and preserve the light. Luckily, it took only a couple months for management to disable the feature.

Building security was equally crude. A guard would open the building sometime in the morning and lock it in the evening. There was no way to get in when the guard was gone. (I suppose that occupants had card access, but there was no accommodation for visitors.) So one frigid winter day—when the temperature was much lower than even what we were accustomed to in New England—I found my colleague Tim Allwine, from our California office, waiting outside the door, inadequately cloaked against the biting wind. He had arrived for a morning meeting, and was rewarded for his promptness by being abandoned to the elements.

I don’t remember any successful cyberattacks on our web site or internal systems during my 28 years at O’Reilly. I may not have been informed if one occurred. But in the Fawcett Street office, one breach was impossible for anyone to ignore.

One day, all the printers started spewing sheet after sheet of garbage text. The administrators ran around shutting them down, then investigated what was going on. They realized that some employee had opened an email attachment with malware. After installing itself on the employee’s computer, the malware copied itself to every other computer on the local area network, where presumably the malware could launch further attacks. This attack vector suggests that the malware’s creator meant the malware to remain hidden, in which case the attacker made a serious mistake. The malware could not tell the difference between desktop systems and printers. When it copied itself to all the printers, they took it as a file to print and thus emitted whatever printable characters corresponded to the bytes in the malware’s binary file.

At some point our management succumbed to the mania for open seating, which had been growing in popularity for some time. I spent most of a decade in cubicles before coming to O’Reilly, and could appreciate the desire to leave behind those indignities. To tell the truth, I could work anywhere and could put all distractions behind me.

Open seating has spawned many debates. It does seem to increase collaboration, while tormenting people who need to concentrate in peace. My impression is that the open seating movement was started by designers in places such as advertising agencies and architecture firms. Here, creativity flourishes in the mingling of many ideas. In fact, before O’Reilly moved to Fawcett Street, the four or five members of our design team took over an open space at Sherman Street and made it their design cave. Because design took on an aura of indispensability during the 1990s and 2000s, leading entire cities such as Barcelona to rebrand themselves as design hubs, I believe that a mania for open seating spread from these creative types to the general office environment where its suitability was much more dubious. In any case, this was the direction O’Reilly took.

Following a plan put together by office manager Rita Scordamalgi and others, we were given some time to pack up. Being told that shelf space would be available, I culled my belongings down to four boxes, mostly consisting of the superannuated books built up over the decades.

The office closed, reopened. When I returned, I found the four boxes next to my mercilessly exposed desk, but none of the promised shelving. So I rid myself of the little sentimentality I had maintained for old translations and other obsolete relics of my work. I offered the books to our donation program (where we send old editions of our books to communities that can’t afford the new editions but can benefit from the preserved versions of the past) and sent my swag to O’Reilly’s archive. I took home a couple boxes of such things such as the overflowing collection of paper clips and rubber bands that I felt too useful to go into the trash, and the few books that held signatures or other meaning for me. The yellow penguin and the soapbox bearing the name LINUX went into my basement.

I was the only person using GNU/Linux in the Boston-area office, although I imagine that some customer support personnel or other techies in the Sebastopol office were using it in some capacity. I was on my own, and the environment proved unforgiving as the GNU/Linux communities strained to keep up with hardware manufacturers and commercial software developers unsympathetic to the operating system. After I installed an early distribution of GNU/Linux, one setting allowed networking while refusing to support graphics, and the other possible setting did the reverse. I forget how I got both networking and graphics to work.

After tiring of making it a second career to tinker with GNU/Linux installations, I took a tip from manager Mike Hendrickson and bought a laptop from Intel with GNU/Linux preinstalled, a new offering from the company. I immediately fell into a black hole in their support, after a routine update to the Ubuntu GNU/Linux operating system shut down the laptop. Intel took absolutely no responsibility for the product they had been happy to sell me, and directed me to Ubuntu forums, where obviously no one knew anything about the Intel installation. I had to wait for another routine update that fixed the problem as mysteriously as it had fallen on me in the first place.

So by the mid-2000s I was ready to give up the pride of ownership in a GNU/Linux system and to take a MacBook from my system administrator.

The other fixture of my time at Fawcett Street was my health club, Mike’s Gym, which I was also ready to give up. There was a time when I would make the 50-minute walk to work, spend an hour at the health club on the stationary bike and weight-lifting equipment, then walk back home. The social environment at the club was also stimulating. I could talk to other men about technology while standing around nude in the locker room. I remember one person asking me, as I was preparing for the shower, “What did you think of the tickle conference?” Luckily, I realized he was referring to a T-shirt I had worn bearing the name Tcl, an obsolete scripting language which was properly pronounced “tickle” and presented an undeserved challenge to Perl for a few years before both were supplanted by the Ruby and Python languages.

Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. also frequented Mike’s Gym for a while. I suppose that this illustrious scholar, like me, was seeking a cheap exercise option. We chatted and I offered him my business card. I learned that he was dealing with serious leg and lower body problems, although I did not realize until I read his memoir Colored People later that he had suffered a serious and long-undetected injury called a slipped epiphysis in childhood. I would have talked to him about it had I known during our Mike’s Gym sojourn, because it so happens that my own child Sonny had experienced the same problem and nearly suffered permanent damage during the several weeks during which we, too, didn’t recognize the problem.

Basically, I liked the Fawcett Street location, even after I had to give up my personal office and take a seat on the floor with forty other staff. But I was rarely working day-to-day with these people.

When our artist worked in the Cambridge office, I found it valuable to meet with him and go over figures together. But he shifted into video production and the figure-drawing function moved to California.

Book production also became more standardized and the design elements became fixed. The production managers discouraged one-off, idiosyncratic designs. So there was rarely a need to meet with the production and design staff, as I often had in the past. The regular weekly meetings I had been forced to attend with my manager or a production manager, luckily, also ceased. These meetings raised problems none of us could solve. Eventually, someone realized that chewing me out over deadlines missed by authors was not bringing in books any faster.

I have already described how we gave up an intriguing, quirky Sherman Street space for the more dependable office environment of Fawcett Street. I thought that a lot of the intriguing aspects of working at the Sherman Street location got left in its dust as well. The new office sported a few enhancements, such as a little game area (also available later in Downtown Crossing) and for a while a 3D printer. But the community wasn’t the same.

There were the requisite holiday parties, but no quirky gatherings such as when an editor visited Italy, wrote a hilarious skit about his experiences, and divided the parts among us to perform in the Sherman Street lobby. Nor do I think the office would come together as the Sherman Street office did on September 11, 2001 as the World Trade Center in New York City fell: A number of us gathered in the lobby holding hands and singing songs of peace from our various religious traditions.

Some of that communal atmosphere had vanished along with Frank Willison; most of the rest failed to find a chink through which to pass the Fawcett Street walls. I felt with some distress the loss of the old culture, and there seemed no way to recapture it.

The final straw came when I entered a conference room for one of our remaining weekly meetings and found myself alone. Everyone else, including a few people right across the open seating area (remember that this was supposed to increase collaboration), chose to phone in. I suspect that people preferred to phone in so that nobody could see that they were working or reading email on their computers throughout the meeting. But I think they also demonstrated a disregard for the communal vitality of a colocated staff.

So I decided I could work from home. The only thing I missed was my gym, but I created my own work-out routine using weights that I could wield in my basement. I let my membership lapse just a few months before the club closed for good—not, I aver, because I abandoned them but because management was idiosyncratic and unpleasant. Many people disliked the owner, although he somehow took a liking to me and helped me somewhat during my stay.

As another historical tidbit, I found that walking long distances became less fun because I could no longer rip music from my CDs to create MP3 files. That change came when Apple introduced its iPod device and its own music service. Apple simultaneously “upgraded” its iTunes product to eliminate the CD-to-MP3 feature. For a long time, after introducing iTunes, Apple had heavily advertised the ability to create MP3 files or your own CDs through a slogan “Rip, Mix, Burn”. But when their new business turned “Rip, Mix, Burn” into competition, they simply made it impossible to do on their computers. Thus I encountered in my daily life the tyranny of non-free software that I had been documenting in my articles.

The question of remote work has popped up at several points during this memoir. I’ve highlighted problems in empathy and communication that can come about when employees are separated, and have rejoiced in my own experiences sharing an office. But I’ve also calculated the heavy costs of concentrating people in one location. O’Reilly has always worked with people from afar, and even before an obscure bat gave us the virus that evolved into COVID-19, collaboration across borders was the way the world has been heading.

Venues have effects on creativity of which we are barely conscious. One venue at O’Reilly is notable in this way: our office building on Sherman Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The next section describes some of the innovative thoughts that floated through this building. But the setting deserves some attention of its own.

The building was called the Brickyard, although someone claimed that it never held a brick-making factory and that the actual brickyard was around the corner on Bolton Street. No matter. Our Brickyard overflowed with old-time charm and quirkiness, like the mill at Maynard where Judy had worked after Digital Equipment Corporation took it over and launched a fad among high-tech companies for remodeling old New England manufacturing spaces.

Our occupancy of the Brickyard was quite recent when I came in 1992. Physically, the Brickyard was laid out around two angled staircases. This design was camouflaged by the walls dividing the companies that shared this old building. One staircase was plunked down in the center of our main lobby, while the other staircase was in the public lobby that led from the street to our entrance. The mirror-image staircases would amuse our children, who came to Christmas holiday parties and circled up and down between floors on the two staircases. Various other doors in the building led to other companies, so that people attempting to pay their cable bills would routinely wander into our office.

Why did the Boston-area office end up here after Tim O’Reilly moved to California? He rented the space from a computer consulting firm whose founder he knew, so the two companies initially cohabited the space and intermingled freely. Because our company grew by leaps and bounds while the consulting firm’s clients dried up, we took over more and more space and finally had a large contiguous area all to ourselves.

Overall, the Brickyard space could be described as funky, with an atmosphere I compare somewhat to a college dormitory. Like university students, we alternated hard work with intimate moments. Years later, my middle-school-aged child Sonny (who later identified as non-binary), in order to raise money for their youth orchestra, brought their viola into the lobby under our staircase and played a cello suite by Bach. I invited everyone in our office and we enjoyed a good turn-out as well as some generous donations. After a couple of movements, I gently suggested to Sonny that they had played enough. I had underestimated the appeal of Sonny’s talent, worried just about boring my friends. The concert-goers protested vigorously that they wanted to hear the rest, so Sonny finished out all six movements.

We were all much closer than mere coworkers. I remember when one woman had a miscarriage, and we put together a scrapbook of personal poems, art pieces, and other artifacts to express our shared grief.

Our technology, apart from Barton Bruce’s intriguing and intimidating racks of servers behind glass, was quite simple. Nobody had a personal computer, as I remember. Instead, each of us sat before a workstation connected by Ethernet to a single SunOS server with the name Ruby. Everyone had system administration privileges, so that if anything went wrong, the person who noticed it could fix the problem right away. All the staff were therefore immersed in the Unix and its X Window System environment (Unix with its corners rounded off, one might say) that constituted the scope of our product offerings.

Anyone who has occupied a historic building has been reading this section with anticipation of horror stories about the problems of working in the Brickyard. And yes, serious difficulties interfered with work from time to time. The building was plagued with all kinds of problems related to water. O’Reilly staff on the upper floor had to tune out the constant noise of workmen shuffling around the roof doing whatever they were trying to do toward the goal of reducing leaks. Bits and pieces of debris would land on desks and workstations. Once the workmen put a huge plastic tarp on one office ceiling to catch water that was dripping in, then forgot about the tarp for several weeks and came back to see it hanging precariously under a load of water. Water problems extended to bathrooms as well.

The technical staff also grumbled about the quality of the wiring available for electricity and our Ethernet cabling, although I did not learn the details and was not aware of any particular burdens the infrastructure placed on our daily work.

After many years, editing became second nature to me, and the challenges of performing my editorial role rested on logistics—just getting the book done. Not only could I quickly see what a text needed—sometimes penning a connective paragraph immediately, other times waiting a few hours in order to bring a more abstract perspective—but I learned how to explain my reasoning in such a way that the author would accept and feel grateful for my changes. I often ran through an initial high-level round of commenting without touching the original text, but always asked for access to the source of the document for a round of more intensive editing.

I invested myself in every book, and it became an element of pride not to cancel a book. Of course, books would disappear from my roster for various reasons, usually because authors got too busy or lost interest as they discovered how hard writing turned out to be. My roster of active books usually hovered around 20, but only six or so actually got published each year; that was enough for me to make a profit for O’Reilly.

Once having trusted an author enough to champion their project and sign a contract, I was loath to tell them they could not succeed. I would simply present an honest assessment of their writing and an opinion about how to achieve our professional standards. If they realized it was beyond their abilities and gracefully withdrew, that was fine. Hardly ever did they persist in bad writing to the point where I or my managers would have to boot them out.

My fidelity to authors may seem excessive, but it has paid off repeatedly. Several times I watched authors blossom as we struggled through difficult passages. For some, English as a second language made their work hard to understand, but they mastered English as we persevered. I usually could tell when poor writing, whether through poor knowledge of English or some other lack of skill, hid real treasures.

The strain of the editorial job lay entirely in meeting schedules. I am proud of the books I brought into the world, but I rue the woeful hours spent with my manager, the manager of production, or both on obsessive scheduling.

This obsession wasn’t arbitrary—publishing can be brutal. During the 1990s, schedules were paramount, and any deviation from a speculative set of deadlines that we negotiated half a year before publication was considered not only a monetary threat but a sort of moral lapse. Bookstores—whose sales were very important during most of the company’s existence—required us to commit to release dates three months in advance. This was understandable because they, too, had to plan their revenues. Barnes and Noble at one point increased this lead date to six months. And missing this date by one month in either direction was highly disruptive. If we were a month late, some booksellers would cancel the order or take down advertisements. If we were a month early, no one would be ready to promote or sell the book when it actually did hit the shelves.

A six-month lead time is probably an easy target for the average publisher of novels or books on contemporary topics. We saw in an earlier chapter the leisurely schedule that Scholastic granted their editors. These generous production schedules could well frustrate authors who watched the conditions they documented change and competing books emerge while their manuscripts sat idly in someone’s inbox.

But technical book publishers such as O’Reilly had very tight production schedules of three to four months, which we were continually trying to shrink. To promise a book long before the author had finished writing the material was not merely difficult—it became an exercise in telepathy.

So I was repeatedly on the hook for some author who was going through a divorce or was suddenly gripped by the impulse to create a start-up company and started missing deadlines. I always implored authors not to do anything during their writing that would put their commitment to us at risk, but they would not put other parts of their careers on hold for a mere book.

What I learned during this time is an appreciation of book development as a time of mutual understanding and growth for both author and editor. A delicate psychology informs the editor’s choice about how much advice to offer and how to make it feel empowering to the author. When the writing process falters, only sensitivity toward the author’s circumstances, and a detailed memory of his patterns of interaction, can help make the decision about when to wait, when to cancel, and when to bring in help. Managers have sometimes been useful in tossing around possibilities and helping to determine responses to authors, but number-crunching offers no solution.

My manager at the time, Mike Hendrickson, once claimed I was passive-aggressive. I can’t prove him wrong, because I have noticed times in my life when I acted passive-aggressively. Some may say that writing this memoir is a case in point. But truly, I do not believe my struggles during these years were passive-aggressive. There were real factors beyond my control that made it impossible to meet all the managers’ expectations.

This explains my annual ratings over the years. People have told me repeatedly that I was O’Reilly’s best editor. I think that’s basically why I survived there so long. But during the many years when management employed a standard five-level rating used widely in many industries for annual reviews (where one “meets expectations”, or “exceeds expectations”, etc.) I never made it into the top level. No matter how many sales I was responsible for or how highly praised my books were, some lapse in scheduling or communication downgraded me in the end.

In our Sherman Street days, the manager Frank Willison became an influential figure. He was our anchor that held the staff together during times of change, and was equally beloved for his sagacity as for his light take on life. Every communication from him contained humor and a profound tolerance.

Whenever a Sherman Street employee left the company, Willison would write a piece of doggerel and read it to an admiring crowd gathered from across the office. Some of those comic poems contained caustic observations that would not have been appropriate to share outside the office. But no one could ever be angry at Willison. He was too good-hearted, too well-grounded, too obviously concerned to do what was right. (The farewell parties disappeared during the following years, and CEO Laura Baldwin eventually told us that she felt it would not give a productive message to celebrate people who were leaving.)

Willison was not alone in performing health checks on his staff. The general ethos at the company was to protect its employees. We felt we were there for our personal self-realization as much as for the product. Such an ideal certainly couldn’t be respected all the time, but I thought that lapses were rare and noteworthy.

Tim O’Reilly often expressed this ideal through the metaphor of a cross-country trip. You need to make sure to stop at gas stations so you can get to the exciting tourist destinations you’ve chosen to see. But the purpose of the trip is the tourist destinations, it’s not a tour of gas stations. In this parable, the tourist destinations represent our job satisfaction, while the gas stations represent profit. Although Laura Baldwin exuded a “let’s get down to business” demeanor that contrasted with Tim’s cool swagger, I sensed that she also put first the health and growth potential of her employees, along with a conviction that the company must keep its mission in focus.

I took special note of Willison’s serious side as my interest in my Jewish background grew and I engaged him in discussions about religion. He told me how reverently he considered the eucharist in his Episcopalian Church. He complained that after blessing the wine and handing out what was needed, the priest would pour the unused wine back into the battle. Willison disapproved of this thrift. He felt that if the church presented the wine as the blood of Christ, it should be treated more reverentially.

Willison unfortunately had health problems. I know that he drank too much caffeine. I remember a dinner we held, during one of our editorial retreats when we were all together from breakfast till lights out. As the waiter came around to offer coffee and desserts, the person next to me ordered decaf coffee. Coming next, Willison told the waiter, “I’ll take the caffeine from his coffee and order a caffeinated coffee of my own.”

His health problems, whatever they were, culminated in a heart attack in his Brickyard office in 2001. Someone tried CPR and a defibrillator, but nothing saved him. Willison’s death was of course a grievous blow to his family. The office staff felt adrift as well. When the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center and other targets followed a little later, we felt that the whole office was at the breaking point. O’Reilly management heard our cry, and scheduled a day-long retreat for all Sherman Street staff. We dealt there with our bereavement as well as with organizational culture and problems we were dealing with day to day.

The variety of projects I describe in this memoir should give you an idea how many doors my career opened for me. I remember, many years ago, being with friends who worked in the computer field and hearing them compare how frequently they changed jobs. One said, “I never stay at any company for more than a few years,” while another said, “I find myself changing jobs on the average of once every eighteen months.” I just said, “My job is different every day.”

Managers at O’Reilly routinely brought people through the Sherman Street office to broaden our outlooks with insights from other fields. One notable visitor was network expert Carl Malamud, a rollicking personality. He later gained fame by publishing records submitted by companies to the Securities and Exchange Commission, thus creating a new era of corporate monitoring. His courageous work might be considered the opening volley in the open government movement, which O’Reilly later championed under its Government 2.0 initiative.

Another surprise visitor was Mai Cramer, well known in Boston as the host of the popular public radio show Blues After Hours. Cramer came not in her role as radio host, but as a designer from Digital Equipment Corporation. I believe she was friends with our chief designer, Edie Freedman.

We also took our intellectual stimulation out of the office—for instance, on a visit to our printing firm. The boldest outings were a couple of wilderness trainings we held at the Habitat Wildlife Sanctuary, run by the Massachusetts Audubon society. Although the sanctuary is just a few square miles in size, it’s enough to feel far removed from urban bustle. In fact, the sanctuary is just a half hour walk from my suburban home, although I didn’t realize that until many years later during the COVID-19 shutdown, when I took long walks for my spiritual and physical health.

Our trainer regaled us with stories of Indian scouts and helped us appreciate the interconnectedness of our environment. We got a sense for how animals, ranging from frogs to bluejays to coyotes, navigated open space. Don’t ask how such lessons make one better at producing computer books, the goal was personal enhancement that could lead to unanticipated contributions to future projects.

With these lessons, reinforced by the mindfulness one of my brothers taught me during hikes in Marin County, California, I decided to strengthen my sense of awareness by going back to Habitat on my own and wandering its paths, once every few months. I followed the teachings of our trainer, finding a quiet spot and staying for half an hour to see what was going on. I noticed that I was increasing my appreciation of the world’s wonders in such simple things as how the layout of trees of different sizes reflected the ways they protected or inhibited one another.

One evening, I noticed the dark falling faster than I had expected (thick trees will produce darkness even when sunlight is shining outside them). I managed to get back to my car before getting lost, but the experience informed a spooky forest scene in my parody of Nathaniel Hawthorne, “The Bug in the Seven Modules”.

I didn’t learn the lesson I needed from this close call, and brought calamity on myself a few months later. I visited Habitat again mid-winter and slipped on the ice coming back. My right leg couldn’t hold my weight, so I crawled the last quarter-mile or so through the snow. Luckily, some other visitors were near the entrance, because I clearly couldn’t have driven away. The visitors got me an ambulance, and the hospital told me that I had broken my ankle.

I was lucky that day. What if I had fallen in similar fashion at night-time, with no one around?

Probably, the ankle that broke had been weakened by an earlier auto accident, just a couple years earlier, a driver had knocked me over as a pedestrian in the dark near my home. Because the auto accident broke my wrist along with my ankle, Judy suffered substantially taking care of me and the whole household, while I spent many weeks trying to train Dragon Dictate to recognize speech. The speech-recognition software is now distributed by Nuance, and has probably seen worlds of improvement. The second break to my ankle did not thrill Judy any more than the first, although the recovery was faster. I decided not to risk putting us in such a situation again, and therefore relinquished my solitary nature walks. Instead, I decided I would expand my world intellectually from my easy chair. I stepped up my poetry writing about that time.

Returning to the topic of my joining O’Reilly & Associates as a full-time employee, there’s a discrepancy between the official record and my own memory of my first day. The official record places my hiring as Monday, November 9, 1992, whereas I remember it being exactly one week earlier, on November 2. No one but an astrologist at this advanced time would care about the discrepancy, and perhaps even the astrologist would consider it an acceptable margin of error.

November 2024: I just found the official letter offering me employment at O’Reilly & Associates. It listed my starting date as November 9, resolving the issue. Still, I might have come in a week earlier on the previous Monday because I was so eager about working there, or wanted to start establishing relationships and setting up my work environment.

What I do remember clearly about that day was the sense of wonder mixed with excitement that I felt upon entering an office that I shared with a long-time employee, Lenny Muellner. In truth, Professor Leonard C. Muellner had earned tenure in the department of classical studies at Brandeis, but supplemented that career with a part-time job doing various technical tasks in our Brickyard office. This information came out during our initial repartee and led later to numerous interesting conversations, such as his cautiously positive response several years later to a news item claiming the discovery of the long-lost grave of the emperor Alexander the Great. By the time the tools team was eviscerated, Muellner had left O’Reilly to take a new job revitalizing the Center for Hellenic Studies at Harvard—a role that eventually brought him around again to digital publishing.

Equally strong in my memory of entering my office was a large cardboard box under my soon-to-be-occupied desk, containing documentation for a company called Cygnus. This was one of the most important companies that entered the early free software movement. Their role was to package and support the compiler tools from the Free Software Foundation. Later they created an environment called Cygwin to run these compiler tools and other Unix-style utilities on Windows systems, a valuable link between those two very different and hostile worlds. But I had no idea why the volumes of documentation should be under my desk. I asked Muellner, “Is every day here going to be as surprising as this?” He laughed in response. Further inquiries around the office let me know that Cygnus was seeking a partnership of some type. I suppose that even on my first day, I was known as a proponent and intimate of free software.

I wrote and edited my first books for O’Reilly as a freelancer. Following my first project, which was to update O’Reilly’s book on the little programming utility called Make, I proposed that the company write a book about a major update to the Fortran language. I had devoted a lot of time to this language at two scientific computing firms I had worked at earlier. Engineers were reluctant to give it up for other languages offering modern conveniences, and the compiler writers tried to give Fortran a new lease on life by incorporating some modern syntax and constructs from other languages. The project was thus called Fortran 8x until it became obvious (as one leader joked) that the “x” would have to be hexadecimal. In the end, they missed the 8x deadline by just one year, and Fortran 90 became a standard.

The company received a proposal from an unknown author named James Kerrigan who wanted to write a Fortran 90 book, and I argued for its approval so assiduously that Tim O’Reilly offered me the job of editing it. I don’t know how I managed to fit in the work while holding down my full-time job and raising two small children, but I had a wonderful time and discovered for the first time the pleasures of building a personal relationship with an author.

Our book came out around the same time as a few dozen other books on the topic by other computer book publishers, all of whom shared with the Fortran compiler writers the optimistic assumption that scientists and engineers would honor many decades of seniority and remain loyal to the language. But none of the books sold at any rate worth the cost of their development.

Still, I had reasons to be proud. There were indications that our book topped the pack, most notably an offer by Microsoft to package an electronic version of our book with every copy they sold of their Fortran compiler (somewhat of an unusual distribution mechanism for a book back then). Our marketing manager, Linda Walsh—in fact, I believe she simply was the totality of O’Reilly marketing in the early 1990s—pursued the Microsoft offer eagerly at first, but ran up against their insistence that they get the book for free. Microsoft arrogantly claimed that merely bundling the book with their product would be such a wonderful endorsement that we should ask for no compensation on top of that. Linda may or may not have known the digital direction that the publishing industry would take later in the decade, but she knew a big swindle when she saw one. Microsoft never got our book.

Walsh was a super connector, an important trait in marketing. She and I were walking between Porter and Harvard Squares in Cambridge one day when we ran into Peter Salus, another super connector in the Unix world. Accompanying Salus at that moment was Rob Pike, one of the inventors of Unix. I wondered at that moment how many famous people I walked by unknowingly every day.

In these first years of my work at O’Reilly, I tend to talk about individuals rather than departments. We were a small company. A department was often an individual, plain and simple. Our international program consisted of a single person, Peter Mui. He did everything that later, at our height, we had six offices working on.

We had a print coordinator in those days, named Sue Willling. Keeping an eye on your printing company used to be a significant job. Although I certainly am no printing expert, I remember several times when things would go wrong. For instance, once we sent a book to a printer who had a degraded version of a font we were using. The printer’s version of the font could not distinguish between an apostrophe and a backtick (a rarely used character). All backticks were converted to apostrophes in the book. Because the book dealt heavily in Unix shell commands, backticks were scattered liberally throughout the book and were most definitely used differently from apostrophes. The book looked fine at O’Reilly, but was completely mangled by the printing company. The author hit the roof, justifiably, and the first printing had to be pulped.

Willing helped us avoid such embarrassments. But increasing standards made it easier to get books printed correctly, and our move to the Internet weakened the importance of a print coordinator. No such position has existed at O’Reilly for many years.

Coming to O’Reilly full-time was a gradual process for me, unfolding over some two years. O’Reilly had always been at the back of my mind because the O’Reilly employee Adrian Nye had written some of the X Window System book series as at the request of my earlier employer, MASSCOMP. The system administrator who set up the MASSCOMP workstation that I would use (not for the high-speed data acquisition the systems were designed for, but for routine testing and book development) told me that my system had copies of the X Window System books Adrian had edited and that Adrian was expected to come back to update them. Not realizing that Adrian referred to a man, I spent my first year or so expecting a woman to walk into my cubicle, say “Hi, I’m Adrienne,” and take over my workstation.

My first glimpse of the new space O’Reilly leased at Sherman Street came a few months before I was hired. Tim O’Reilly seemed quite proud of the office, which was a big step up in size and professionalization over his previous office (not to omit the barn), and he wanted to show me around before interviewing me over lunch. This was not a formal interview, but more like a free exchange of ideas. We went out with a couple other people, including Mike Loukides, who had recently been hired as an editor.

Tim chose the nearby Joyce Chen’s restaurant. I thought how there were a few other Chinese restaurants that were much better. I believe I was rude enough to suggest that to the head of a company who was about to hire me, and who was paying for lunch to boot. I don’t remember the topics of conversation, probably because the computer field has changed so much and our understanding of it has evolved so richly since then that it would be almost as hard to re-enter the mind of a young technologist in 1992 as to relive the experience of a two-year-old child.

Tim had no need to interview me, having employed me on a freelance basis for some time already. My luck in landing the job at his company was a textbook illustration of the old boy’s network. About a year and a half after I arrived at MASSCOMP, the technical writers’ management job fell on Steve Talbott. Talbott knew Tim O’Reilly well, and he certainly knew Adrian Nye’s work at MASSCOMP.

I wrote up some of my adventures at MASSCOMP, and especially my relationship of mutual trust with Talbott, in a chapter of the O’Reilly anthology Beautiful Teams many years later. Talbott was impressed by my mastery of tools, particularly the odd Unix utility called Make that was used to automate builds in an age before integrated development environments. It was coincidental that I designed my own build tools around this utility and that Talbott had written a 70-page book on it called Managing projects with make for publication by O’Reilly. He could not help but notice my creativity with both technology and writing. So he asked me to write a new edition of his book for O’Reilly. Not realizing what an honor that was, or for that matter how much work it would demand, I launched in and successfully finished the project at the perfect time: the week between the end of my employment at MASSCOMP and the start of my next job.

The book on Make conformed to two themes that have run through this memoir: the shock of unexpected tasks and finding a creative response. The shock was to discover that many different versions of Make were out in the field. It was only after finishing my draft and sending it out to technical review that I learned from my reviewers that the job was much bigger than I expected—that in fact it involved a whole new dimension of explaining differences between versions of the utility. Not only would Make behave differently on different computer systems, but many users wouldn’t know which version they had.

How could I offer instructions to readers when the program’s behavior was unpredictable? I took an eminently practical and creative solution: I provided a script that readers could run to determine which features were supported on their system. This script turned out popular in its own right.

At the end of the 1980s decade, MASSCOMP faded into irrelevance due to changes in the computer industry. It became either beneficiary or victim of an acquisition and gradually lost all its talented employees. Talbott made his way out before me, and after taking a job as an editor at O’Reilly called me and urged me to join him. But I felt more empowered working in the computer industry directly, rather than at a remove in a publishing company. Talbott explained that I would rub shoulders with the very leaders of computing by joining O’Reilly, but I rejected the advice at first and spent a year and a half at another company, the U.S. computer subsidiary of Hitachi mentioned in other stories.

I do not regret that detour, because I took responsibility for much tool development, got comfortable reading the source code for the Unix operating system, and learned to navigate Japan social mores. But problems both at Hitachi and the environment in which Hitachi operated soured the situation, and I gradually pulled closer to O’Reilly & Associates.

Meanwhile, I started to seek (years before the availability of web sites for personal self-expression) a way to air my opinions about the important interactions between technology and society. After joining O’Reilly I reserved the praxagora.com domain name, hoping to maintain a web site that would offer a broad forum for opinions and insights about computer technology. For Talbott, I hosted a good deal of online essays about his views on computers, which ironically were quite negative.

Talbott was a competent computer technologist who earned a living creating value in computing but consistently warned about its risks to human consciousness and society. There is nothing new about such contradictions. J. Robert Oppenheimer ran the Manhattan Project in order to provide the free world with a defense against Hitler, but then spent the rest of his life trying to rescue the world from the atom bomb that resulted. Computer Professionals for Social Responsibility, where I spent the bulk of my volunteer efforts for 15 years, warned constantly about the downsides of the technologies in which we were expert, as did the Association for Computing Machinery’s policy group. But Talbott was more of a Cassandra than the rest of us.

It turned out that no one else asked me for space on the web site associated with praxagora.com, and Talbott eventually moved his content to a different host. This was the right thing to do, because my view of computing and Internet access was largely laudatory while his was cautionary. But for twenty years, I kept a pointer on my web site to Talbott’s the new site.

MASSCOMP was apparently unaware that O’Reilly & Associates had absconded with the books Adrian Nye had written on MASSCOMP’s dime and had thrown aside contract writing to develop the X Window Series into a massive money-maker. This story provides a tale of free content and commercialization.

The historic importance of the X Window System was its universality. The Unix operating system had developed for several years with no interface except a text-based green screen experience. Users learned tools such as Make at the command line and used editors such as my own beloved Emacs in full-screen mode. There were few graphical systems and no standard for graphics until a team at MIT created the X Window System. Their invention became the graphical interface for all Unix systems and still plays a role in the version of Unix offered by Apple for its Macintosh systems. Of course, it was free software, released under the MIT License with the simple mandate to go forth and multiply.

Suddenly a raft of tools beginning with the letter “x” became part of the Unix user’s toolset, and with this came an urgent need for documentation about how to create more x’s for the Unix world to use. MASSCOMP had hired Nye to beef up the MIT documentation and make it more professional, as well as to write a series of programming guides that Nye produced with great aplomb. There is no doubt that he was a master of the difficult art I was also trying to practice, that of readable and actionable documentation for computer professionals.

O’Reilly’s coup came from permissive licensing. On the MIT side, they let people do whatever they wanted with their documentation and did not require (as the Free Software Foundation does in their GNU series of licenses) that all changes to distributed versions of the code or books be contributed back to the original creators. O’Reilly could therefore intertwine MIT’s massive contributions with the improvements made by Nye and others and put the O’Reilly copyright on it.

Furthermore, MASSCOMP management made no thought as to the value of documentation outside their own company. They imposed no contractual requirement on O’Reilly to ask permission or pay any licensing fees when O’Reilly commercialized the X Window Series. Had MASSCOMP requested a modest licensing fee in exchange for their funding of the project, their financial prospects would have been much better.

The X Window Series became transformational for O’Reilly. The company could now devote itself purely to publishing and quickly became a household name in the Unix field. Companies such as Sun and Hewlett Packard, expecting their workstation users to create X programs as a matter of course, bought up crates of O’Reilly X books and provided a full set (the series ultimately reached about nine volumes) with every purchase of a workstation. When the common X core splintered a bit and generated a variety of extensions, O’Reilly could afford to rewrite some of the series in different versions.

This exploitation of intellectual property has a curious parallel with another leading company in the tech world: Microsoft. Bill Gates started his company to provide IBM with an operating system for its new personal computer. Numerous companies had witnessed the popularity of early kits and cobbled-together personal systems. All these companies were pushing their offerings on the market in the early 1980s. IBM, an improbable contender because it was a mainframe company, wiped out the competition not through any technical superiority, according to many analysts, but simply through the faith that major corporations continued to place on these three familiar letters.

IBM produced software as well as hardware, but perhaps lacked confidence in their ability to provide an operating system for this tiny device. They somehow discovered Gates, and he licensed software from somewhere else and provided it under the name MS-DOS to IBM. Again misunderstanding the value of software—which they were used to distributing for free—IBM left total control over MS-DOS to Gates. And as knock-off PCs emerged from other companies, MS-DOS became the default standard for everybody. Although IBM throughout the 1960s and 1970s was a feared monopoly and a target of U.S. government anti-trust action, the age of the PC saw the end of an IBM monopoly and a shift toward the dominance of the two features all PCs had in common: Intel chips and MS-DOS, followed by Microsoft Windows.

O’Reilly is quite different from Microsoft. The publisher had established a stronghold in computing with a highly respected line of Unix books like the one I edited, Managing projects with make, before they started the X Window System series, and they never attained the impregnability in their industry that Microsoft enjoyed for decades. Both stories, however, show the power of control over key resources and how a shift in value can turn long-disregarded side products into indispensable commodities.

Thus it was that I joined Nye at O’Reilly instead of Nye joining me at MASSCOMP. Nye played an important editorial role until he decided that his life’s passions took him out of publishing. He adopted early on a concern for climate change, which we all had heard of but was not in the 1990s the clear danger to life that we later recognized. On the other hand, Nye was learning how to fly a plane and loved that hobby. After he left, one of my fellow employees mocked Nye’s professed concern for the climate, dubbing him “Private Plane Nye”. But I have never seen a contradiction between adopting one or two carbon-producing elements of lifestyle and caring about the Earth. All of us contribute more carbon than we should to the atmosphere, and we know that the solution cannot come from individual sacrifices but from a collective change to the whole structure of the economy and society.

For Nye to sacrifice his plane, or for any one of us to sacrifice a long commute to a job where we do good or the loving gesture of giving someone flowers would mean to relinquish our individual creativity. To emerge from climate disaster, particularly at this seemingly impossible moment, requires extraordinary and probably unpredictable accomplishments from the human race. The crisis calls on all the innovativeness, all the passion, all the personal investment of heart and mind that we can muster. That joy in creation was what Tim O’Reilly and his company celebrated from the beginning, what kept me there for nearly three decades, and what gave me the platform and the unlimited mandate to contribute to so many causes.

If the computing history in this memoir interests you, check out some other articles where I cover specific historical topics: